The corpus of Frisian runic inscriptionsGeographical, runological and linguistic features can be used to determine whether or not an object with runes is of Frisian origin. Apart from some objects that have proven to be falsifications, the corpus that is agreed upon, consists of over twenty items. In 1939 Arntz and Zeiss were the first to describe a Frisian runic corpus, which consisted of the nine items (1) known at the time and was published in their work Die einheimischen Runendenkmäler des Festlandes. They also considered the skanomoducoin to be of Frisian origin. To Arntz and Zeiss the most important feature to define an object as Frisian was that it had to have been found in Frisian territory.

When Tempel came to Leeuwarden and Groningen in the 1960’s to look at the bone combs kept at the Frisian and Groninger Museums, he discovered that some of them had runic inscriptions on them that were overlooked to that day. The corpus he and Dűwel described (Dűwel & Tempel, 1970) could therefore be extended with another four items, as well as with some recent finds. They were also the first to to underline the -u ending as a criterion for the Frisian runic corpus. A more recent description of the Frisian runic corpus is by Quak (1990). His nineteen items were disputed by Looijenga’s checklist (1996). The corpora agreed on eighteen items, but Looijenga did not recognize the Eenum bone to be Frisian and added Hamwic and Wijnaldum B. In her thesis (Looijenga 1997) she added another object, the Midlum bracteat, bringing the total of Frisian runic objects to twenty-one (2). Whether eighteen or twenty-one objects are agreed upon, the corpus remains very small, certainly if compared to the dozens of runic stones found in Sweden. Most runic objects we know of, have been found in the second half of the 19th century and first half of the 20th century, the period when in Friesland and Groningen the terps were dug out for their fertile soil. This waterlogged terp-soil is also believed to be the reason that these objects have been preserved rather well. The materials used to engrave runes in Frisia were mainly bone or wood. Apart from the five coins, no Frisian inscriptions have been found on precious materials, like gold or silver in the shape of jewelry or weapons. All Frisian objects are portable (no standing stones) and have been dated - for as far as possible - from 400 to around 800 AD. The objects are generally known by their finding place, so a coin comb found in the terp soil of the village of Kantens, is named Kantens, a coin found near Schweindorf (Germany) is called Schweindorf and so on. In two cases, more objects have been found at the same place. They have been given an alphabetical numbering: Westeremden A and B and Wijnaldum A and B. This list of Frisian runic finds is based on the corpora of Arntz & Zeiss, Dűwel & Tempel, Quak and Looijenga. It is believed that king George III had a coin in his possession, which he may have brought from Germany. It became part of the collection of the British Museum. As the original finding place is not known, the coin is named Skanomodu after its runic inscription skanomodu (skanomodu, name, meaning 'great courage', or 'beautiful mind'). Not only does it have the Aglo-Frisian a, it is also one of the best examples of linguistic features in a runic text, as it has both the a sound (which replaced the Gmc. au) and the -u suffix. As the coin is dated 575-610, it is thought to be the oldest recorded Frisian word. Folkestone is believed to have been lost at the British Museum7. Another example of the coin is kept at the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow. It has the inscription aniwulufu (aniwulufu, a name) and dates from around 650. Apart from the presence of the a-rune, the ‘Frisian’ au > a monophtongization is present in this legend.

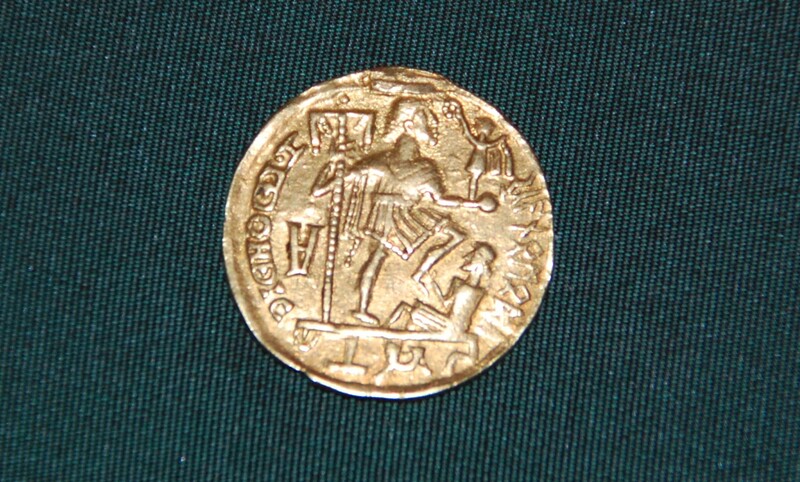

The Schweindorf solidus was found in 1848 and was cast around 575-625. The runic text is weladu, with the typical -u ending. The Harlingen solidus (6th c.) has the runes hada cast on it, the h is double barred and both a’s are typical Anglo-Frisian ac-runes. The most recent find of a coin is the Midlum sceat, dated at 750 with the runic legend apa. Interesting is that these sceattas are rarely found north of the Rhine. This one is and what is more, there are Frisian features in the runes, with the a and a rune. Ferwerd is an antler comb from the 6th century, without any particular AngloFrisian runes in the inscription mura (mura) but found in Frisian terp soil. The a rune could stand for Germanic a, but could also be a OFr æ. The Frisian origin of the Amay comb is under debate because of its finding place (Belgium). It does have the Anglo-Frisian a-rune in its inscription 'eda' (8). Apart from this rune, it is suggested that the shiny surface of the bone comb is the result of it having been buried in Frisian terp soil, before it was buried at Amay. The runes on the Hoogebeintum comb remained unnoticed for years, because an adhesive label with the inventory number was stuck on the inscription. It is not known what the runes mean. The finding place is the sole reason to regard this object/inscription as Frisian. The bone combcase from Kantens is the oldest rune find in Frisian territory, dating to the early 5th century. There are only two runes, the first is agreed upon to be an l, the second rune could be an i or a w, but the inscription is too small to be intelligible. The Oostum comb (8/9th century) actually exists of two halves, both sides have been inscribed. Side a) reads alb kabu (ælb kabu) , side b) reads deda habuku 9(deda habuku), which could mean: ælb’s comb, made (by) habuku. In this case the use of the AngloFrisian a and a-runes, as well as the finding place make this an undisputed Frisian runic object. The inscription in the 8th century bone comb of Toornwerd includes the o-rune in the inscription kobu, ko(m)bu10, a legend that is very recognizable as ‘comb’. Westeremden A is a weaving slay of taxus wood which has not been dated. The inscription is very hard to distinguish, but some of the known ‘Frisian aspects’ are the finding place (province of Groningen), a double barred h, an a rune and monophtongization of au > a (in adu). Westeremden B is an undated, little, threesided stick of taxus wood, with inscriptions on two sides. Although the meaning of the inscription is hindered by some unique runes, the Anglo-Frisian a and o runes are present. A miniature sword of the late 8th century found at Arum shows the inscription eda 2 boda, edæ : boda. Several translationas are possible, as edæ could be a name or be related to the word oath. Looijenga (1996) suggests oath-messenger, as it is known that a sword was used to swear oaths on. Another little stick was found at Britsum (no date), with a rune that could come from the younger futhark and represent k, although others have suggested a vowel should be read. Certainly an Anglo-Frisian o is present and an a that could be read as a Frisian æ. The function of the ivory object found at Hantum is unknown. It is interesting that besides a runic inscription, one side has an inscription with roman characters: ABA. The runic inscription i2aha2k is hard to interpret. As the date of the object is unknown, it is also unknown whether the a-rune has to be interpreted as a Gmc a or an OFr. æ. Rasquert (province of Groningen) is a symbolic swordhandle (whalebone) of the late 8th century. It’s inscription contains the aand o-runes and a a-rune which has the ævalue. On one side the inscription has been erased and the other side is badly weathered. Rasquert

Wijnaldum A - a piece of antler - also has other inscriptions besides runes. In this case ornamental crosses, squares and triangles. The runic inscription is rather incomprehensible, as it is embedded in a cartouche and some runes could be mirrored.

These are the objects Quak and Looijenga agree upon (11). One object has been found since the publication of Quak’s list. Wijnaldum B is a gold pendant of ca. 600 with the inscription 'hiwi'. Remarkable is are the h-rune that only has one diagonal bar and the w-rune of which the loop is not closed. Another horses bone-piece, a knucklebone, found at Hamwic (Southampton) carries the inscription katæ. According to Looijenga (1997) the runes on the Eenum bone-piece of a horse's leg, described by Quak, turned out to be just scratches, perhaps slaughtermarks. Criticism of the Frisian corpus Certainly when compared to the wealth of Scandinavian runic finds, the Frisian runic corpus is rather small. It is also significantly smaller than the English number of finds (around seventy inscribed objects) and the Southwestern German number (about sixty objects). Even more, the Frisian corpus lacks runological uniformity as not all of the objects show the Anglo-Frisian runes. Some objects, like the Westeremden B yew wand, have very particular runes, that haven’t been found anywhere else. Some of the inscriptions are too small to interpret, others are longer but still hard to understand. It is no wonder that some people have cast doubts over the question whether or not to recognize these twenty objects and their inscriptions as being typically Frisian in origin. Professor Nielsen from the University of Southwest Denmark has criticized the corpus of Dűwel & Tempel (12). First of all he pointed out multiple-line runes on Britsum and Wijnaldum A, which are also found on an amulet found at Linsholm and a spearshaft found at Kragehul. These Scandinavian influences on the Britsum and Wijnaldum A inscriptions had been disregarded by Dűwel & Tempel. Furthermore Nielsen disputed the Frisian origin of some inscriptions, on the basis that there were no indications for it to be Frisian, other than the assumption that they were: Harlingen, Arum, Hantum and Amay could just as well be English. Looijenga (1997) does not agree with Nielsen as he discards the Frisian corpus because of it “hotchpotch of geographical, archaeological, numismatic, runological and linguistic criteria”, as she finds that this is also the case with other corpora. Nielsen’s claim that the monophtonization au > a is not typically (Old) Frisian, but can also be found in Old Saxon, has been criticized by Gilliberto (1998). She states that in Old Saxon the au > o monophtongization is predominant and the au > a form can only be found in “sources with a greater adherence to the Ingveonic roots and, consequently show a greater affinity to Old Frisian”. Nielsen also disagrees with the theory that the -u ending is a Frisian linguistic feature, since there is no evidence for it in the oldest Oldfrisian manuscripts. Gilliberto agrees with him on this point although no other inscriptions with this u- ending have been found outside Frisian territory, apart from the Skanomodu and Folkestone coins. Generally speaking, I feel there is a strong case to recognize the objects described above as Frisian. As long as a clear distinction can be made between different corpora, there is no problem recognizing a Frisian corpus. Distinction can be found in the finding place, as eighteen of the twenty-two described runic objects in this essay, have been found in Frisian territory, ie. the provinces of Groningen and Friesland, and Ost- Friesland. The Anglo-Frisian runes set the Frisian objects apart from other corpora, like the Southwest German or Scandinavian ones, though not from the Anglo-Saxon corpus. One needs to combine the runological features with the geographical finding place and/or linguistic features to narrow the Anglo-Frisian corpus down to a Frisian one. The objects that combine geographical, runological and linguistic aspects, form the ‘backbone’ of the Frisian corpus: Oostum, Toornwerd and Westeremden A. If Nielsen’s criticism of the u-ending as a Frisian feature is accepted, Westeremden A would be the only one combining geographical, runological and linguistic aspects. In the cases of Folkestone, Amay, Hoogebeintum, Kantens, Britsum, Eenum, Wijnaldum A en B, the evidence is limited to just one aspect, mostly the finding place. It is easy to doubt the Frisian origins of these objects, as there is no guarantee that they have not been imported from elsewhere. It would be worthwhile to see how the other corpora have been defined, but that’s beyond the context of this essay. In my opinion a critical look of the Frisian corpus is certainly appropriate, but with fourteen objects that include two or even three Frisian features, there is no need to doubt the existence of a Frisian runic corpus. 4 Looijenga, 1997, 35 5 Arum, Britsum, Ferwerd, Hantum, Harlingen, Westeremden A and B, Wijnaldum (A) and Amay 6 Looijenga also lists the Bergakker find, which I consider not to be Frisian, since it doesn’t bear any Frisian runological or linguistic features 7 Looijenga, 1996; according to the curator Early Medieval Coins the Folkestone tremissis was not lost, but is in a private collection 8 Dűwel & Tempel (1970) and Looijenga (1996) and Quak (1990) suggest that the inscription ‘ade’ should be read from right to left: ‘eda’. 9 the actual h-rune has three diagonal bars and the b-rune has three bows 10 as was often done in runic inscriptons with m and n, the m in this legend has been left out 11 Different objects have turned out to be falsifications, like the Jouswier bone plate (falsification), a bronze book-mounting (scratches turned out not to be runes), an item, probably a stone, with the inscription hilamodu that has once been described by professor Brouwer, but the whereabouts of the object are unknown, Westeremden C (in private possession, not accessible for inspection) and the Hitsum bracteate (although authentic, it’s not Frisian, and may be related to Northern German bracteates). 12 Nielsen, 1996 << Frisian Aspects of Runes Corpus of Frisian Runes

|